Network analysis as a way to understand the global shape of the IU Community

Everything around us is connected. In the same way that maps , networks show us how people, events, objects, places, and even ideas are connected together by the relationships between them. Network analysis is a way of visualizing this interconnectedness and exposing connections that might be less obvious otherwise.

Networks helped us answer our research question because we could use both place and other keywords that came with the objects to tie communities together.

--H301 Fall 2019 student

We build networks by putting together “nodes” (points) and “edges” (the lines connecting points). Every node in the network represents one thing, whether it’s the Declaration of Independence, Beyoncé, a flower pot, September 11th, or love. Every edge connecting two nodes represents a relationship, showing that the two things are connected in some way. As we analyze a network, we can see how important a given node might be based on the number of its edges, which tells us how connected it is to other nodes. Finding the most important nodes and connections helps us discover a broader story - a story that might only appear when we look at the interconnected whole as more than simply a sum of its parts!

We used a program called Net.Create to analyze the network data from our History Harvest, but anyone can make their own network with just a pen and a piece of paper. Try drawing your social network as it exists today, with you at the center and your friends and family (and anyone else you are connected with) as nodes connected to you (and potentially, each other!). How would you draw the same network from a point in your childhood? When you compare your two networks, how might they help you see changes to your social networks over time?

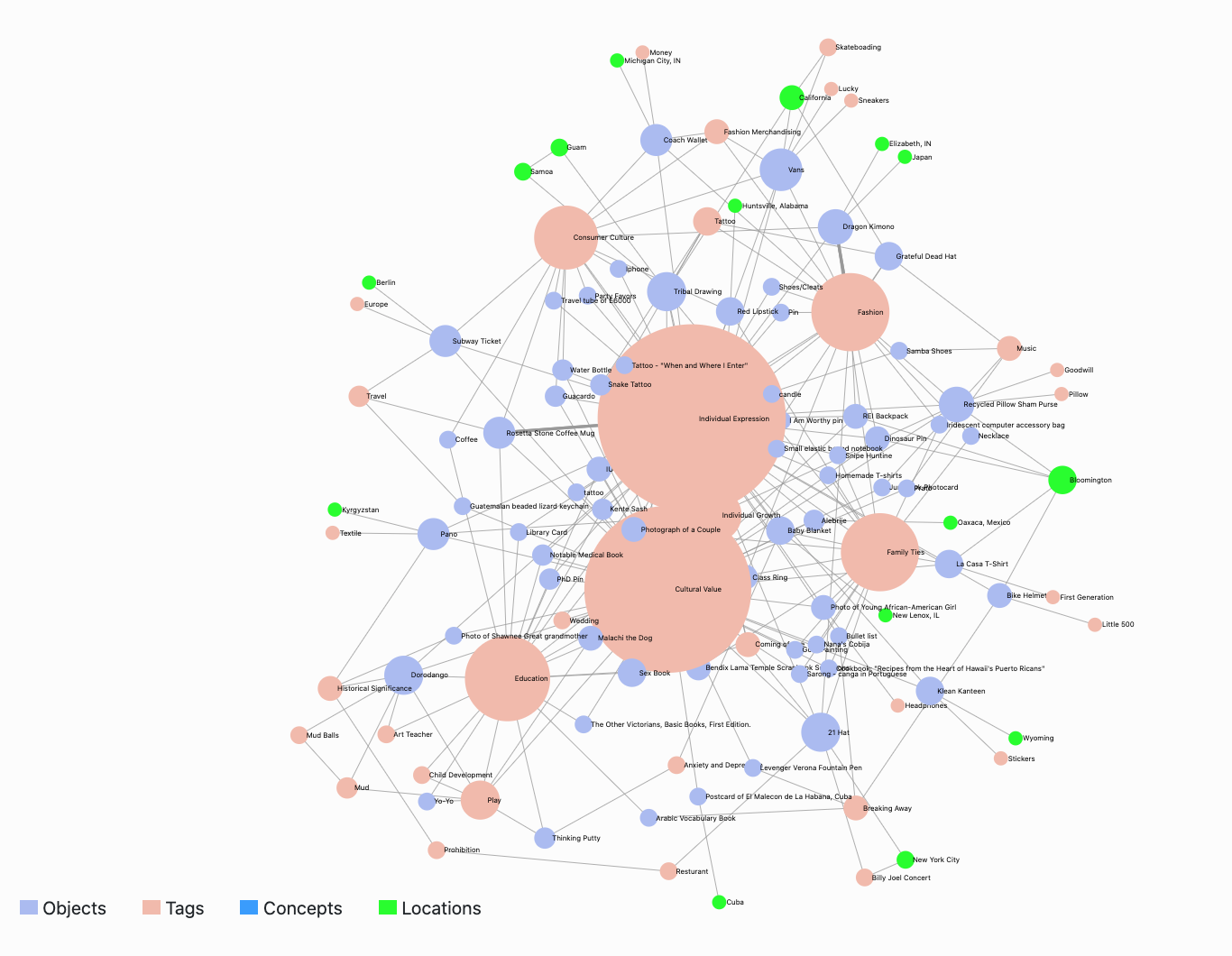

Fig 1: One group started with a looser taxonomy using objects, locations, and tags as nodes with a broader “is connected to…” edge type. This research group’s goal was to see connections between the objects and the tags develop as they entered data from the collected objects. Our method was for each group member to focus on one item at a time, create a node for that item, create nodes for tags and locations relating to that item, and then connect that item to those nodes. Once each member added all of the tags and locations for the object and connected them via edges, we moved on to the next object on the list.

Fig 1: One group started with a looser taxonomy using objects, locations, and tags as nodes with a broader “is connected to…” edge type. This research group’s goal was to see connections between the objects and the tags develop as they entered data from the collected objects. Our method was for each group member to focus on one item at a time, create a node for that item, create nodes for tags and locations relating to that item, and then connect that item to those nodes. Once each member added all of the tags and locations for the object and connected them via edges, we moved on to the next object on the list.

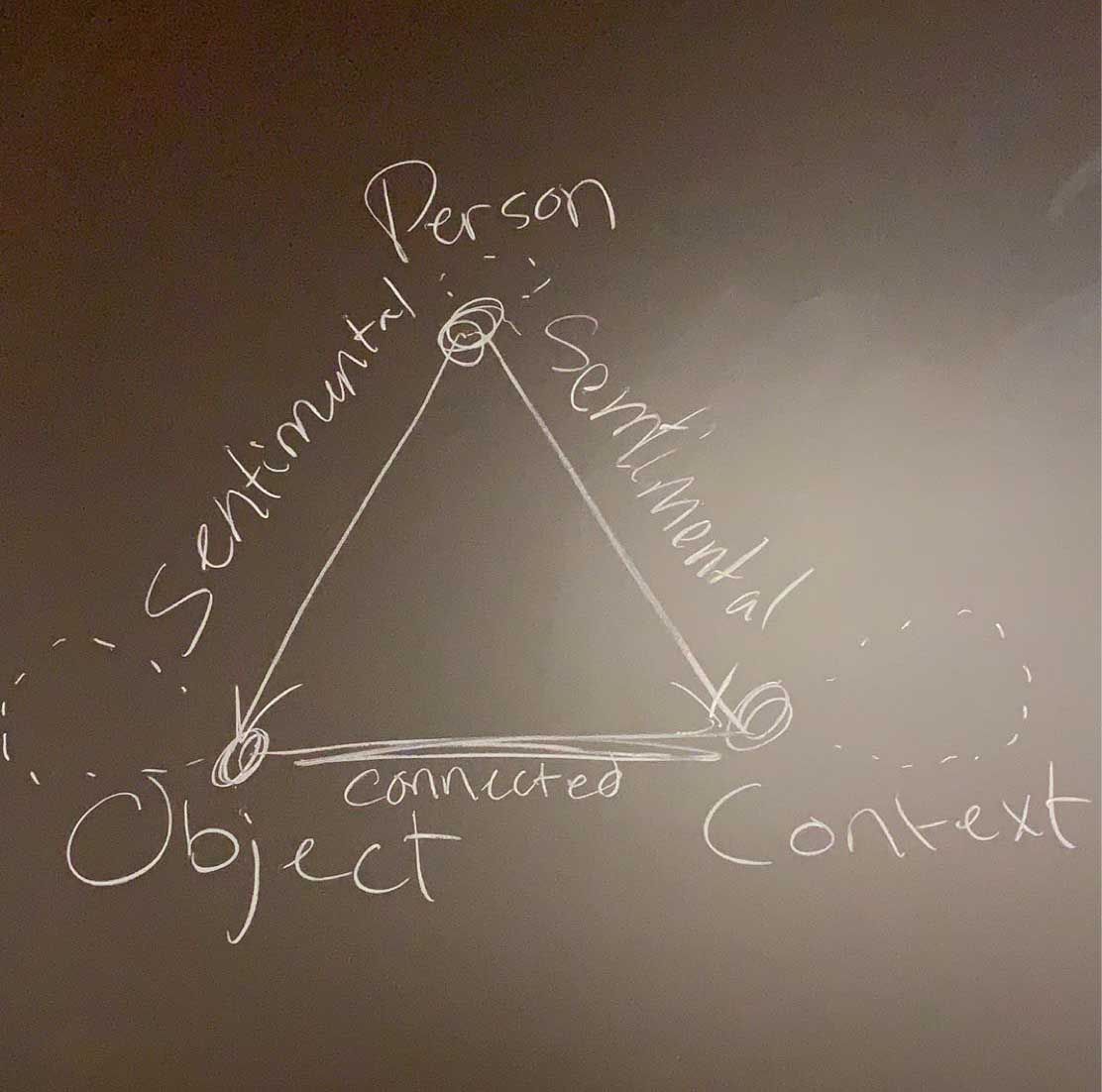

Fig. 2: Another group hand-sketched a base model on a blackboard (digital recreation shown above) depicting how objects, their contributors, and their significance might link together to see how they would all connect to a larger sense of community here at Indiana University. Using this model, the student researchers were able to explore how seemingly different objects all came together here at Indiana University, from their different cultural backgrounds and different locations around the world. This led us to divide our objects based on their cultural context, individuality, and/or location of origin. Not all of the objects fell into all three of the categories; some only fell into one.

Fig. 2: Another group hand-sketched a base model on a blackboard (digital recreation shown above) depicting how objects, their contributors, and their significance might link together to see how they would all connect to a larger sense of community here at Indiana University. Using this model, the student researchers were able to explore how seemingly different objects all came together here at Indiana University, from their different cultural backgrounds and different locations around the world. This led us to divide our objects based on their cultural context, individuality, and/or location of origin. Not all of the objects fell into all three of the categories; some only fell into one.

One of the beautiful aspects of network analysis is that it allows us to use the same information in service of different approaches to create and interrogate it in a network. Take the two networks above from our class. Both groups had the same data gathered from the History Harvest. Notice that one group looked at that data and decided that one way to organize and study it was through Individual Expression and Cultural Value (Networks Group 2) and the other group decided to focus on Sentimentality (Networks Group 1) to understand Culture in Context. Think back to your two networks now, could you think of more than one way to look at your social network today? During a moment in your childhood?

Networks allow us to see the underlying connections that are not always present on the surface. As we began to collect the information during the History Harvest, we learned more about how our contributors and what they contributed were connected. From interviews about their contributions, we learned a number of things: where they obtained their object, where they were from, how their object connected them to a community, and why they decided to bring that specific object to us. With all this information, we were able to start connecting the objects’ journey.

The two student groups who worked with our History Harvest and network analysis ended up asking two different questions:

- How do meaning and sentimentality factor into the objects an individual owns? read more...

- How do objects that people and communities own reflect the societies they are in? read more...

Student group 1’s research was structured around a model that pre-supposed the types of connections that might exist between a contributed Object, Person, and Theme, with Location as an extra node type that helped the group understand how the person felt their object provided a sense of identity or community.

Student group 2 took an organic approach to their question about the balance between individual self expression and cultural connections by drawing on metadata–descriptive information that came with each of the contributed objects–like keywords and location information. Each of the objects and each of the keywords became nodes, and the group quickly honed in on the tension between individual self expression and the broader cultural values that shape individual expression.

While Groups 1 and 2 took different approaches to developing their research questions, and as a result, built networks that linked very different types of information about each object, the two groups found common ground as they explored where their networks differed and converged. Looking at both of the networks together, and accommodating new node types and new edge types, . Let’s walk through it here, edge by edge:

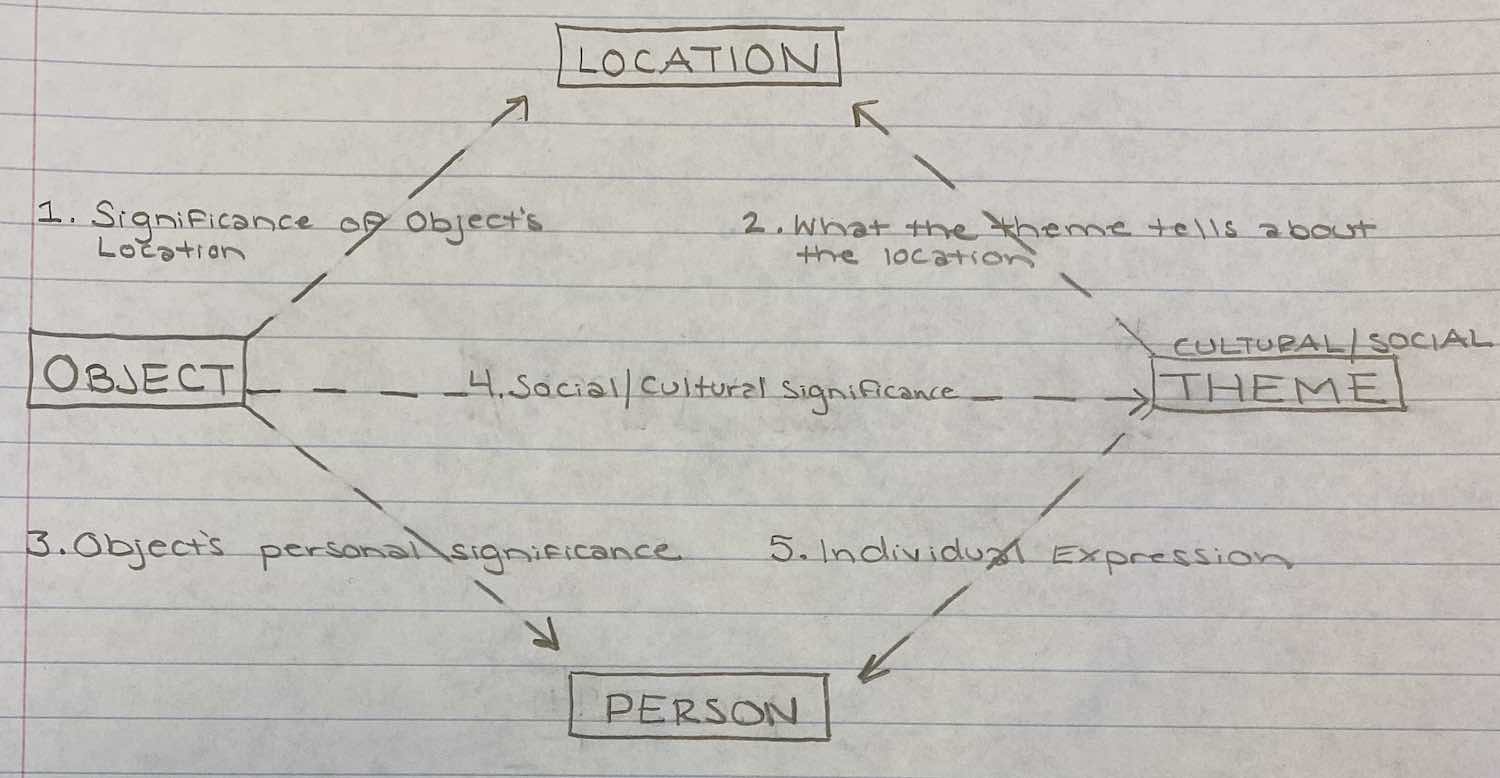

Above, you can see a potential model that emerges when we combine the models and patterns visible in both networks. Four areas of focus start to come together to paint the picture that the two different networks created: Object, Location, Theme, and Purpose. Group 1’s focus on Individual Expression and Cultural Value highlights three of these categories: Object, Location, and Theme. The Objects and Location aspects are straight forward; what is the object and where does it come from? The Theme category is where their method of research and organization starts to come together; what do the objects have in common, or, what are their purpose?

The connections between Object and Location nodes help us see when an object’s location matters to the contributor (and when it doesn’t). This was particularly important when we considered sentimental attachment to places and spaces based on whether an object was handmade or manufactured. We were also able to use this connection to explore the value of specific places as a factor of gift giving. When we combine Object, Theme and Location, we get an even more complex view of the ways in which an object’s broader significance, both as a representation of individual values and a community’s cultural norms and expectations, might be shaped by the community from which it originated.

When our model also accommodates connections between the Object and the Person, we can also ask questions about the personal nature of mass-produced objects and explore the impact of global trade and industrialization on a personal level. The mass printing of a cookbook, the manufacture of a commercially produced kimono, and the customization of factory-line cleats all offer broad insight into the histry of the modern capitalist world, but they also link individual people into that bigger picture.

Let’s take one last look at your networks. If you asked a question about your social network today, what would it be? How would it show you how your networks connect across time, space, and activity? Ultimately, our two projects asked different versions of the same question: “how do the social/cultural influences of an object tell a story about how the contributor expresses themselves?”

Our answer? Networks let us see the larger connective structures that are hidden beneath the one-on-one interactions we have every day, like tunnels running underground. Each one of those connections helps us build a better understanding of belonging, identity, and community.